Toronto’s hot housing market has created a dilemma for the baby boomer generation. With home prices verging on the unaffordable for many young couples, should boomers ante up and help their kids buy a new property in the city?

To begin with, let’s consider home prices in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The average price for a detached home in downtown Toronto is $1.2 million. A semi-detached home costs $817,000 and a townhome goes for an average of $623,000. Even a condominium will cost new owners an average of $416,000. That’s a far cry from even 10 years ago, when prices were about one-third of what they are today. The problem is that salaries haven’t tripled in that time period. Not even close.

The GTA is heading into the spring home buying season with soaring demand and a shortage of listings, said Cliff Iverson, head of the Canadian Real Estate Association, whose data shows an 11.6 per cent increase in home prices in Toronto this year compared with 2015.

But today’s millennials feel a sense of entitlement when it comes to home ownership. After all, previous generations were able to buy a house, usually with enough bedrooms for children, so why not them?

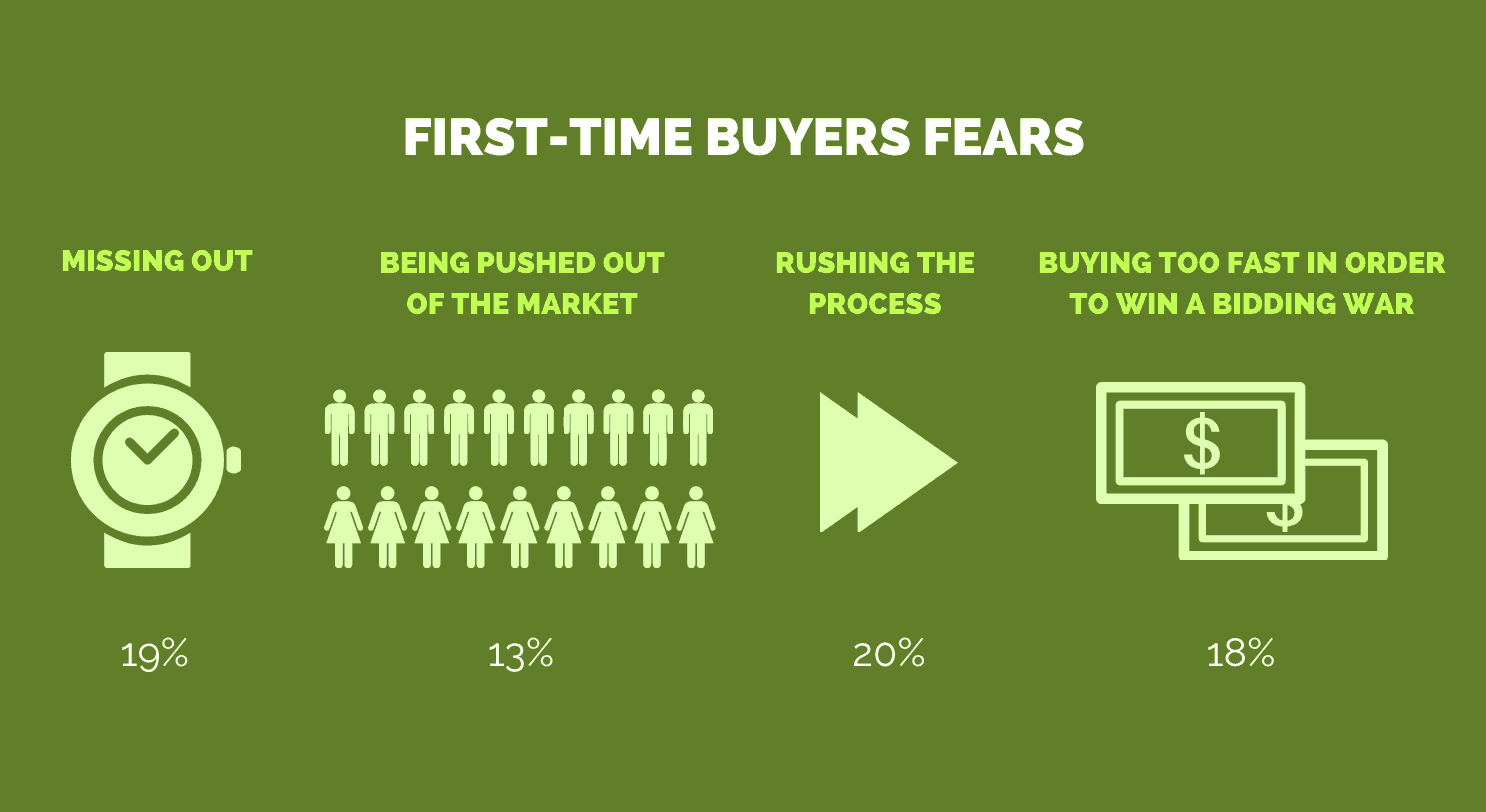

Fear of missing out

A recent TD Bank survey found that 19 per cent of homeowners listed "fear of missing out" as a top consideration when making their first home purchase. And 13 per cent were afraid of being pushed out of the market. On the other hand, 20 per cent of first-time buyers were worried about rushing the process and 18 per cent feared buying too fast in order to win a bidding war.

"The busy spring home buying season can create competitive bidding wars, and research suggests that prospective buyers are already worried about rushing the process," says TD’s Marc Kulak. "There's more to consider beyond purchase price, interest rate and the monthly mortgage payment. It's essential that buyers leave enough time to do their homework—especially considering 40 per cent of prospective first-time buyers are worried they don't understand the full cost of ownership."

Kulak recommends that first-time homebuyers save for the largest down payment they can afford, even if that means waiting a bit longer to buy. "The larger the down payment, the less you will need to borrow, which ultimately saves you money in interest payments long term. With a down payment of at least 20 per cent, buyers can also save on mortgage insurance premiums upfront."

A 20 per cent down payment on a semi-detached home in Toronto equals a whopping $163,400. Can young couples afford that? Even with both members of the family working full-time, a 20 per cent down payment is often simply out of reach, not to mention the mortgage payments and other home ownership costs.

That’s where the question of borrowing from your family to buy your first home comes in.

Taking care of boomers

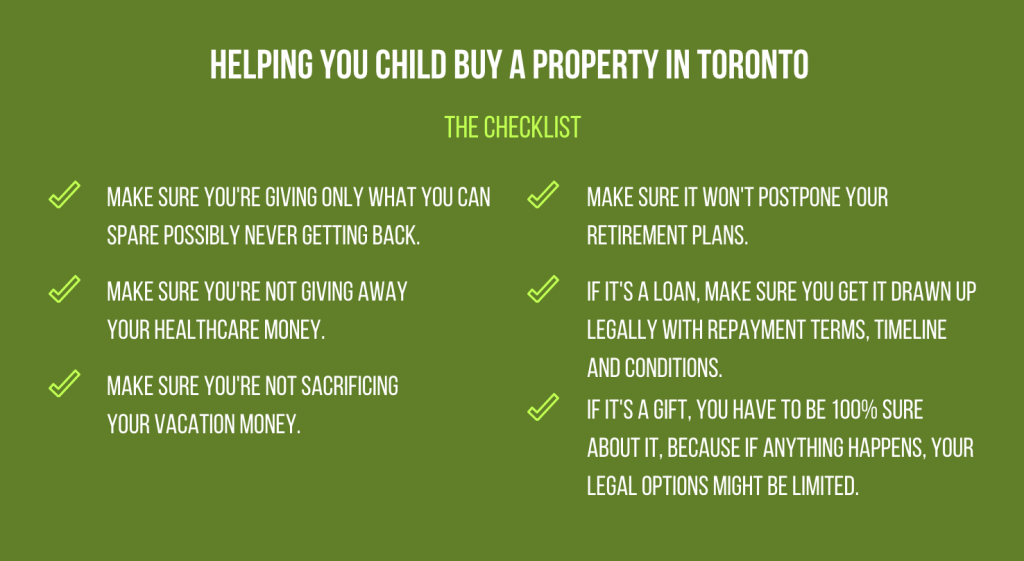

Toronto-based Kurt Rosentreter, financial advisor, Manulife Securities, says he has lots of boomer clients facing this question. "And I say we’re here to take care of you first," he says. "So how far do you want your own financial goals and your children’s financial goals to collide? Because often, these can be material sums of money in a way that they can affect the primary client’s retirement plans."

If you decide you can afford it and not impact your retirement plans, Rosentreter says the next step is to decide how to do it.

You have to take care of the parents first.

He suggests a zero interest loan unless you have absolute confidence that your child will never have any relationship issues. "And of course nobody can say that," he points out. "What a family lawyer will tell you is that if the relationship doesn’t work out, it preserves the loan to come back to your family rather than it going to an ex-spouse."

Rosentreter says a loan may be the only way a boomer’s kids will ever get into a new home, considering they are staying in school longer and the jobs available after graduation just don’t pay enough to put a down payment on a house, at least right away. A study by National Bank suggests that it will take 6.5 years for the average working couple to save enough for a down payment on a semi-detached Toronto home. That’s a long time to wait.

"It’s a tough call for people who may have to postpone their retirement plans to help out their kids but that’s where we’re at," says Rosentreter.

Still, Rosentreter believes that if the parents need the money for their own financial well-being, then they shouldn’t even be considering a loan.

That’s where the conversation has to start; you have to take care of the parents first. You can’t give away their healthcare and vacation money, that’s just not right. And I know some parents will override those concerns and do it anyway, but that’s not the way it’s supposed to be.

Rosentreter says the kids may also need a dose of reality, noting that many have never seen anything but a low interest rate environment.

"When I do the math for these kids, maybe with a household income of $140,000, and you look at the size of the mortgages they are taking on in the 416 and the 905, when does common sense kick in and say, you can’t do this? You may be able to stretch the payments today, but if interest rates ever go up over this 25-year amortization period, you could end up bankrupt."

Rosentreter has calculated that a 1 per cent rise in interest rates could mean a 20 per cent increase in mortgage payments.

And there won’t be much money left over after you’ve paid the mortgage for other necessities, such as furniture, a car and vacations. That can be a stressful place to be in your relationship when there’s no other money for anything else.

If the parents can’t afford a loan, Rosentreter says the kids are simply going to have to wait longer until they can afford a larger deposit, pushing out home ownership into their 30s and even 40s. "And as I’ve said before, maybe we have caught up to New York and London; Canadians may need to change their approach and consider renting for life."

Playing the devil’s advocate

Jeanette Brox, a CFP and Toronto-based financial advisor says the loan issue has also been a topic of discussion in her practice.

"It’s always nice for parents to help their kids out and to see them enjoy the fruits of their hard-earned labour, meaning instead of waiting to give the kids money when they die, they can see them enjoy it while they are still here," she says.

But, she adds, people are living longer and if you’re going to start giving your kids money for a down payment, let’s say $100,000, "that’s really going to impact on what your retirement might look like."

Helping your kids buy a property will have a great impact on your retirement.

Brox plays devil’s advocate with her clients, pointing out that they may get ill and require long-term care insurance, or the home they’ve put money into might fall into limbo if the kids’ relationship falls apart.

"Your intention was not to give that person who hurt your child half of the house. But they will get half of the house. It’s a dicey situation and you could get around it by putting the house in a trust, but there’s a cost to doing that. It’s not a straightforward issue."

Brox provides an example of a young couple looking at an $800,000 home in Toronto. As mentioned above, that would mean a down payment of about $160,000. Then they’ll be faced with a mortgage of $640,000 with a monthly payment of around $2,800. Although two working professionals should be able to afford that, what happens if one gets sick or loses their job? "There are no guarantees," Brox says. "And the divorce rate is 63 per cent."

Putting all other issues aside, Brox says you have to decide if a loan is a good idea in the first place. If it is, then the difference between ever being a homeowner may be mum or dad helping out, she adds.

"And if they are going to do it, a loan is the best way and I think the dollar amount must be respectful of the fact that mum and dad want to retire someday."

A realtor’s perspective

Tyler Delaney

Tyler Delaney, a sales representative with the Julie Kinnear Team in Toronto, says it’s a competitive market for first-time homebuyers and he works closely with millennial clients in the city, noting that most have the assistance of their parents, whether it’s help with the down payment or co-signing the mortgage. "Having parental help is key for a lot of people these days," he says.

The baby boomers benefited from low housing prices so they have built up a lot of equity in their homes, he explains. So homes purchased in the 1970s and 1980s for $100,000 or less are now worth more than a million dollars.

"Those homes were paid off a long time ago and they’ve got all this equity built up, and the plan is to pass it to their children anyway, so why not help them now and see them benefit while they are still around?" he asks.

Delaney gives the example of a young couple who are both actors and trying to get their careers started, so they don’t have the consistent income to qualify for a mortgage, never mind the down payment, so their parents are supplying half the costs of the home and are partners in the remaining 50 per cent, so any growth on that property will benefit both sides.

"Depending on the relationship between the parents and the child, there are different options out there for them," Delaney says. "Real estate is the most reliable investment you can make, so it’s a good financial decision for parents to help their children and to grow their net worth and equity in their homes."

DW00SK